Hand-Crank Generator DIY STEM Kit

$9.99$4.95

Posted on: Feb 11, 2005

Contrary to conventional wisdom, technology’s advance into the vanishingly small realm of molecules and atoms may not be out of sight for the venerable optical microscope, after all. In fact, research at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) suggests that a hybrid version of the optical microscope might be able to image and measure features smaller than 10 nanometers—a tiny fraction of the wavelength of visible light.

In a preliminary test of the embryonic technique, NIST scientists used violet light with a wavelength of 436 nanometers to image features as small as 40 nanometers, about five times smaller than possible with a conventional optical microscope.

Roughly speaking, such a feat is akin to picking up a solitary dime with a clumsy front-end loader. If successfully developed, the imaging technology could be readily incorporated into chip-making and other commercial-scale processes for making parts and products with nanometer-scale dimensions.

The wavelengths of light in the visible part of the spectrum greatly exceed nanoscale dimensions. Consequently, the resolution of conventional light-based imaging methods is limited to about 200 nanometers—too large to resolve the details of nanotechnology, which, by definition, are no more than half that size.

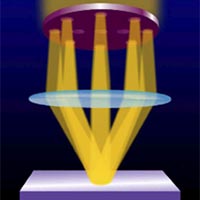

Resembling a 3-D checkerboard, this mirage-like pattern was formed by light waves after bouncing off a specimen with a peak-and-valley arrangement of etched lines. Such complicated wave patterns, the result of light scattering and interference effects, may be used to discern the dimensions of nanoscale features.

However, a newly begun, five-year research effort at NIST suggests that a novel combination of illumination, detection and computing technologies can circumvent this limitation. Success would extend the technology’s 400-year-long record as an indispensable imaging and measurement tool well into the expanding realm of nanotechnology.

Called phase-sensitive, scatter-field optical imaging, the computer-intensive technique under development at NIST uses a set of dynamically engineered light waves optimized for particular properties (such as angular orientation and polarization). How this structured illumination field—engineered differently to highlight the particular geometry of each type of specimen—scatters after striking the target can reveal the tiniest of details.

“The scattering patterns are extremely sensitive to small changes in the shape and size of the scattering feature,” explains Rick Silver, a physicist in NIST’s Precision Engineering Division.

'When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion

that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than my talent for absorbing

positive knowledge.'

'When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion

that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than my talent for absorbing

positive knowledge.'