Solar & Battery Fan DIY STEM Kit

$9.99$5.95

Posted on: Jun 11, 2010

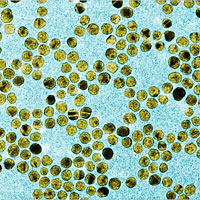

Gold nanoparticles — tiny spheres of gold just a few billionths of a meter in diameter — have become useful tools in modern medicine. They’ve been incorporated into miniature drug-delivery systems to control blood clotting, and they’re also the main components of a device, now in clinical trials, that is designed to burn away malignant tumors.

However, one property of these particles stands in the way of many nanotechnological developments: They‘re sticky. Gold nanoparticles can be engineered to attract specific biomolecules, but they also stick to many other unintended particles — often making them inefficient at their designated task.

MIT researchers have found a way to turn this drawback into an advantage. In a paper recently published in American Chemical Society Nano, Associate Professor Kimberly Hamad-Schifferli of the Departments of Biological Engineering and Mechanical Engineering and postdoc Sunho Park PhD ’09 of the Department of Mechanical Engineering reported that they could exploit nanoparticles’ stickiness to double the amount of protein produced during in vitro translation — an important tool that biologists use to safely produce a large quantity of protein for study outside of a living cell.

During translation, groups of biomolecules come together to produce proteins from molecular templates called mRNA. In vitro translation harnesses these same biological components in a test tube (as opposed to in vivo translation, which occurs in live cells), and a man-made mRNA can be added to guarantee the production of a desired protein. For example, if a researcher wanted to study a protein that a cell would not naturally produce, or a mutated protein that would be harmful to the cell in vivo, he might use in vitro translation to create large quantities of that protein for observation and testing. But there’s a downside to in vitro translation: It is not as efficient as it could be. “You might get some protein one day, and none for the next two,” explains Hamad-Schifferli.

With funding from the Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, Hamad-Schifferli and her co-workers initially set out to design a system that would prevent translation. This process, known as translation inhibition, can stop the production of harmful proteins or help a researcher determine protein function by observing cell behavior when the protein has been removed. To accomplish this, Hamad-Schifferli attached DNA to gold nanoparticles, expecting that the large nanoparticle-DNA (NP-DNA) aggregates would block translation.

She was discouraged, however, to find that the NP-DNA did not decrease protein production as expected. In fact, she had some unsettling data suggesting that instead of inhibiting translation, the NP-DNA were boosting it. “That’s when we put on our engineering caps,” recalls Hamad-Schifferli.

It turns out that the sticky nanoparticles bring the biomolecules needed for translation into close proximity, which helps speed the translation process. Additionally, the DNA part of the NP-DNA complex is designed to bind to a specific mRNA molecule, which will be translated into a specific protein. The binding must be tight enough to hold the mRNA in place for translation, but loose enough that the mRNA can also attach to the other molecules necessary for the process. Because the designed DNA molecule has a specific mRNA partner, that mRNA in a solution of many similar molecules can be enhanced without having to be isolated.

In addition to enhancing in vitro translation, Hamad-Schifferli’s NP-DNA complexes may have other applications. According to Ming Zheng, a research chemist with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, they could be combined with carbon nanotubes — tiny, hollow cylinders that are incredibly strong for their size. They may ultimately be the cornerstone of transport systems that ferry drugs into cells or between cells. The stickiness of the NP-DNA might enhance the speed and accuracy of such a drug-delivery system.

Although Hamad-Schifferli is confident that her discovery will make in vitro translation more reliable and efficient, she is not done. She hopes to tinker with her system to further enhance protein production in vitro, and see if the system can be applied to enhance translation in live cells. To help reach these goals, she must design and conduct experiments to determine which molecules are involved in the enhancement process, and how they interact. “The upside is that we’ve been lucky,” Hamad-Schifferli says, reflecting on her discovery. “The downside is that it will be difficult to tease out exactly how the system works.”